The science behind Frames

Introduction

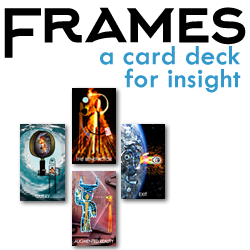

This article outlines a few of the scientific reasons behind why the Frames card deck works so well for you.

It’s always good to have new tools like Frames. We’re a tool-making species and our peripherals–software, wetsuits, aircraft, child car seats–extend our ability to grow, protect, and understand life. Despite all the tools and technology, generations still ask themselves: What’s my purpose? If we all die, why work so hard to leave the world a better place? Frames can help you take action on those questions.

Below I’ll offer some science for each stages of a frame, which are:

- Question

- Randomizing (shuffling) the deck

- Selecting 4 cards

- Interpreting the visual allegory and symbols

- Consulting your intuition

- Resolving to an action

The big questions

Frames starts with a question that is intensely personal to you, and one that you want to take action on.

I have been an avid reader of Science News for decades. Since the 1980s, studies in apoptosis, or genetically-regulated cell suicide, have caught my attention. I wondered, how do single cells know what to do, when, and why? I looked for underlying principles. I discussed it with my children when they became upset with roadkill or when walking through fallen cottonwood leaves (neither which is induced by apoptosis, but, hey, it was a teachable moment about lifecycles). Apoptosis came to mind when faced with personal or social randomness such as a massive birdfall in central Texas in 2003 or a neighbor committing suicide in 2016. Why had this concept stuck with me?

This same question is examined in an article in The American Naturalist on “How an Organism Dies Affects the Fitness of Its Neighbors” which considers the effects of programmed cell death (PCD) in the fitness of its neighbors [1]. Okay, it’s genetic programming…but it includes an odd keyword of altruism. Like these researchers, I, too, was looking at the answer, desperately turning my head to catch a glimpse as it just evaded my sight.

Then, I saw it. Like cells, the byproducts of our life and death have purpose. Our costly altruism of collecting personal damage is “a resource for others.” The first Frames card I created was the Bug card for this reason. It was a symbol of patient, hidden purpose. Like the bug, the answer you want exists—in cells, in trees, in stars, in humans—but the timing and manner of it emerging is a mystery. Debuggers can only keep searching.

Randomizing the deck

After selecting your question, an essential process of the Frames deck is shuffling the 45 cards. Like most games with a finite set of elements, the players want to produce the most fairness among participants and reduce the reoccurrence, or weighting, of cards that have previously appeared. However, there is no “winning” in Frames, so why shuffle? Why not just lay them face up and choose what seems attractive?

If you honestly want to work on your question, you want to be surprised.

Surprise feels random, unexpected. The definitions of what “random” means varies but we all seem to know how it feels when it occurs: as an external force that confounds our ability to predict an outcome, or even a pattern. A short paper on intuition and randomness describes one of the few times psychics and technology experimented together (the Zenith experiment). Stanford researchers Griffiths and Tenenbaum argue that people identify and prefer chance–surprise–in many situations over predictability because of

the flexibility that we allow in identifying meaningful relationships. Together with the fact that everyday life provides a vast number of opportunities for coincidences to occur, our willingness to tolerate near misses and to consider each of a number of possible concurrences meaningful contributes to [our] explaining the frequency with which coincidences occur [3].

So when posing a Frames question with an uncertain outcome, why do we add in more uncertainty and chance by shuffling?

It’s because our important questions never feel resolved by thinking logically, making lists, argument, and attempting to predict all possible outcomes. Random cards seem of a kind with the general randomness of life, so perhaps we can embrace it closer and use it as a tool?

Selecting 4 cards

Selecting the 4 cards for a frame is done by the person asking the question. At this point, if they have shuffled adequately, they have some confidence that when they spread out a line of cards they do not know which cards are where in the line. They choose 4 cards, based on the positions of the frame: person, unconscious, conscious, and action.

The important factor is that THEY choose the cards and not someone else.

A recent study of decision-making by researchers at Berkeley Wills Neuroscience Institute calls this “neuro-economics,” or the lightning-fast stream of evaluations we make based on its costs and benefits to us [4]. They use dopamine to chemically test which areas of the brain control what types of decisions.

Expecting a reward after making a choice, no matter how small, lights up chemical signals in the brain [5, 6] and leads to us feel in control of our choices and outcomes. It’s been linked to the placebo effect in some studies. As one of the more studied effects of decision and interaction science, dopamine is front and center when making selections and getting rewards, whether opening a gift or imagining what’s on the back side of a Frames card.

A recent book by Melanie Warner called “The Magic Feather Effect” (2019) is a good overview of alternative forms of healing, placebos, and the ways we connect expectations to outcomes [7].

In the Frames deck, the expectation that you have agency (power) in your life, that a problem is solvable (or at least approachable), is perhaps the most important aspect of Frames. You expect to be delighted and surprised with a random card, and you are. The allegory (explained below) tickles your sense of mystery and connection to the unknown parts of your life. You selected the cards that are moving your life forward one yard at a time.

Symbols, Semiotics, and Allegory

The 4 Frames cards are laid out in the positions and the player now begins to interpret each one.

An allegory is a text story or artwork from which you can gather a meaning [8, 9, 10]. A common text story among many cultures is the contest between a fast and a slow animal. A common visual allegory is the Statue of Liberty or a climber on a mountaintop. Allegory when it’s applied to a figure, like Batman, is personification where meaning can be made from that figure alone and their actions. The meaning of an allegory can be applied to many situations, often adapted to fit the particular life lesson. The general imagery is accompanied by fine detail that has even more meaning.

Frames specifically does not include gender on the cards. Gender is a visual allegory in which we have been conditioned to make cultural meaning from appearance or role of the person. I believe that accurate answers to your questions must clear any cultural filters caused by gender in the artwork.

Retrieving your inner data

How do we answer questions that seem to be “right there” but elude us?

The Frames deck has 45 illustrated cards with unique titles. The titles are drawn from modern, common concepts that we interact with every day. This frequency and modernity is critical.

The ideas are drawn from science and technology, such as Password, Student, or Network. As the video at right demonstrates, the more frequently you interact with an idea, the more firmly a “pointer” to your inner data is written.

When asking a question for a frame, your brain is rapidly sorting, filtering, and comparing the visual data on the card with your memory, your inner data. The gap between the conscious question and the missing data is connected.

Your perspective on inner data may be based in the physical–that our chemically-based bodies lay down memory trail and we store data bits for retrieval. Or it may be based in the philosophical–that we co-create our own consciousness with others or that consciousness and memory is more of a quantum, neither/nor state [2]. Either way, we have a shared behavior of wanting to know, knowing, forgetting, and retrieving our own data. We cannot retrieve the memories of someone else.

Listening to your intuition

Citations:

- Durand, Pierre M., Armin Rashidi, Richard E. Michod, Associate Editor: Franz J. Weissing, and Editor: Ruth G. Shaw. “How an Organism Dies Affects the Fitness of Its Neighbors.” The American Naturalist 177, no. 2 (2011): 224-32. doi:10.1086/657686.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fjbWr3ODbAo The Illusion of Consciousness

- Griffiths, Thomas and Joshua Tenenbaum. “Randomness and Coincidences: Reconciling Intuition and Probability Theory.” Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. (2001) http://web.mit.edu/cocosci/Papers/random.pdf

- “Decisions in the Brain.” Review article in Berkeley Neuroscience News, June 15, 2015. http://neuroscience.berkeley.edu/decisions-in-the-brain/

- “Making Choices: How Your Brain Decides.” 2012. http://healthland.time.com/2012/09/04/making-choices-how-your-brain-decides/

- “Imagination Medicine.” Erdmann, Jeanne. Science News. Dec 5, 2008.

- Warner, Melanie. “The Magic Feather Effect.” 2019

- https://edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/allegory-painting

- https://arcade.stanford.edu/content/personification-and-allegory-0

- https://www.illustrationhistory.org/genres/comics-comic-strips

Symbols, Semiotics, and Allegory

kjAbf

VR and the brain: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/virtual-reality-therapy-has-real-life-benefits-some-mental-disorders

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/ripples-brain-memories-recall